Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, ancestral land of the Querandíes, es rebonito (super pretty). We arrived there on day 107 of the Israeli attack on Gaza. The occupation continues at full force, despite the fact that the International Court of Justice has ruled that Israel must “take all measures” to avoid acts of genocide in Gaza. The siege and deliberate targeting of hospitals — as well as areas previously defined as “safe zones” by Israel — have led to the collapse of the healthcare system, and people are dying of famine and disease, not only from Israeli strikes. Meanwhile the US and the UK, along with several other countries in the Global North, have stopped funding the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA).

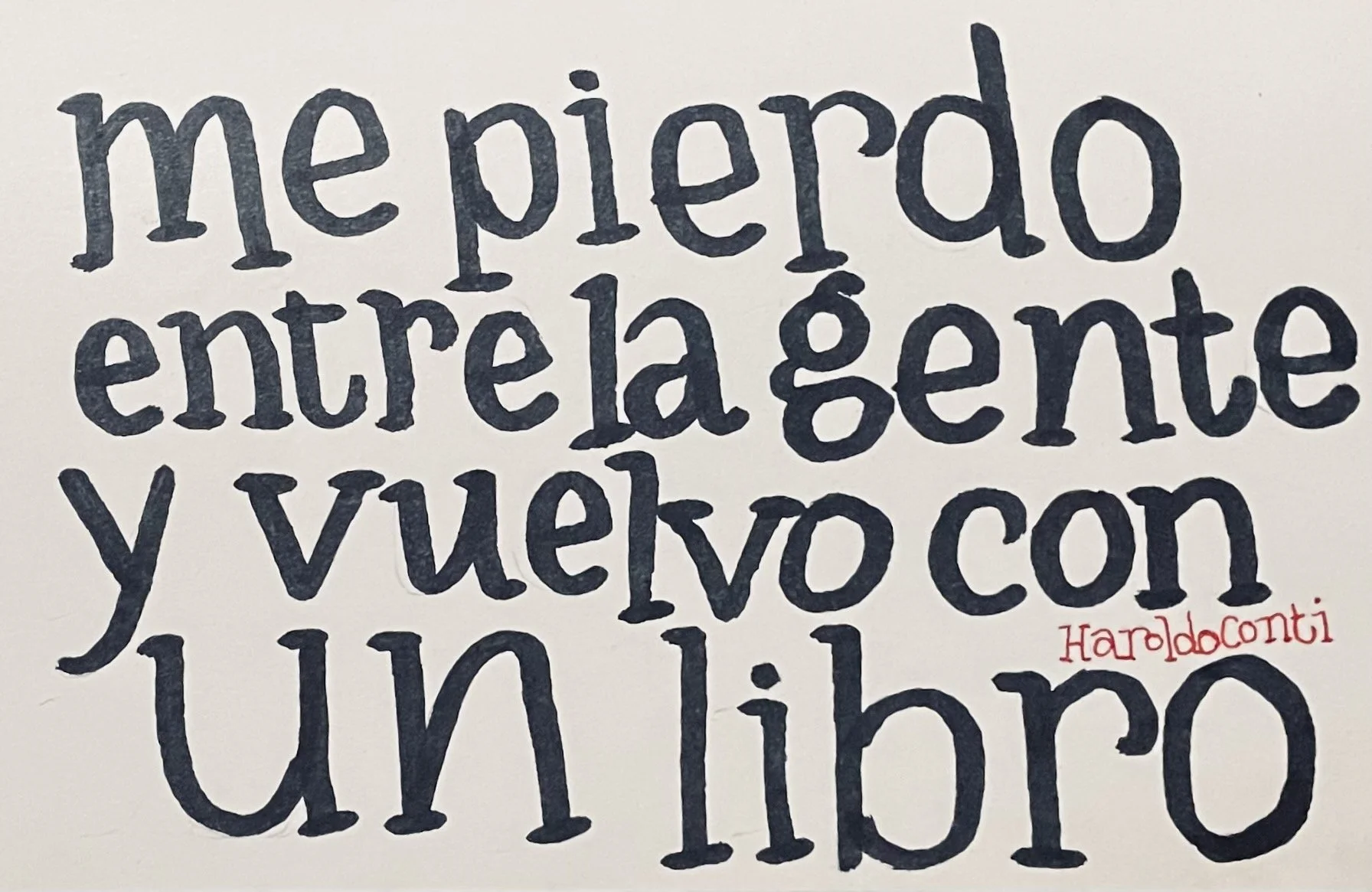

Haroldo Conti Cultural Center for Memory

Buenos Aires was officially founded by the Spanish in 1536 but due to fierce resistance from the Querandíes the settlement was abandoned in 1541. In 1580 it was founded again, given the need of the Spanish Crown to have a safe route to the Atlantic, and this time the settlers came ready to exterminate the indigenous peoples of the land.

If Santiago and Manila are sisters of my native Bogotá, I found Buenos Aires to be more grandiose and yet I felt like I could also tune in to its pace and frequency. One thing I noticed is that it has green parks everywhere, many of them with big statues of lady republics or military men, and I loved that once you reach the shores of the La Plata River it extends all the way into the horizon.

The big avenues and boulevards around Congress, and Avenida de Mayo in particular, reminded me of Montpellier — I had never been to Buenos Aires but I have lived in Europe on multiple occasions and the architecture of that part of the city was very familiar to me. The Monument to Bartolomé Mitre felt like Trocadero, for example, and there is a tall obelisk in the Plaza de la República. At points while in Sam Telmo I really felt like I could be home walking around Central London.

Of course there is more to Buenos Aires than just a European aesthetic, and I know there is so much more to know. My dad and I went to the Recoleta Cultural Center and it was so vibrant, with people hanging out until late and enjoying the fresh and evocative art on the walls. Walking down a big avenue we found two giant metallic close-up portraits of Eva Perón (the iconic Argentinian politician and activist), each of them displayed on a different side of a tall white building. We saw beautiful street art, a mural in particular commemorating 46 years since the coup and recognizing the 30,000 people disappeared by the military regime. In the mural there are several people holding a banner that says, “Memory is the homeland that we dream of”. Adorning the number 46 is a second banner that says, “Not forgetting // Nor forgiving” Someone tried to cover the mural with black paint.

We walked around the San Telmo market with its many smells, stands and restaurants and ate delicious food. We visited the Cathedral and I took in its majestic angular pink stone columns and flower-themed mosaic floor. (Catholicism does not really do it for me, but I was raised in a Catholic family, and my mother always sends the Virgin and the angels to care for me. So I go into Catholic spaces thinking always of my mom and grandparents, and praying to the ancestors, asking that they care for me. My professor Drucilla Cornell, who died in 2022 has joined my ancestors, too.) We walked to the Plaza de Mayo, a big square surrounded by gorgeous palm trees, facing the Casa Rosada (Pink House, literally pink and home of the President). Since the dictatorship, the Madres (Mothers) and Abuelas (Grandmothers) of la Plaza de Mayo gather at the square to demand justice for their disappeared children and stolen grandchildren.

We went to the Espacio de Memoria y Derechos Humanos ex ESMA (Space for Memory and Human Rights, formerly ESMA). The place served as the Mechanical School of the Army, and during the last military regime it was used to hold suspected political opponents to torture and disappear them. It is a gigantic military complex, with big signs everywhere commemorating the lives of the people disappeared there.

We went to the Casino de Oficiales, where the highest ranking officers lived and which was the main place they held prisoners. The façade of the house has been covered with a structure of glass with many faces of those disappeared or killed by the military engraved on it. It reminded me of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago.

In 2,818 days the dictatorship disappeared 30,000 people in over 700 detention centers. That is so many people. The same number of people estimated to have been killed by Israel in Palestine since October 7.

I often think about our complicity as people from the US in this genocide, funded in great part through our taxes. In ex ESMA, I learned about the role of the US and France in the terrorism of state techniques used by the Argentinian military against the people.

At the end of the 1950s as part of the war against Communism, the Argentinian Army adopted the French counterrevolutionary doctrine, perfected through the French war against “internal enemies” in Algeria and Indochina. In the museum, there is also a copy of the Student Guide for the School of the Americas, the infamous US counterrevolutionary training institution for soldiers from across Latin America and the Caribbean operating since 1946 where many Argentinian soldiers were instructed on how to destroy any suspected oppositional organization.

One of the images displayed in the museum shows a fútbol between two tall wired fences. Below it reads, “PAS DE FOOTBALL ENTRE LES CAMPS DE CONCENTRATION” (NO TO FÚTBOL IN CONCENTRATION CAMPS). The boycott against the 1978 World Cup in Argentina did something very important: It put in the newspapers of the world the horrendous Human Rights violations taking place under the military dictatorship led by Jorge Rafael Videla.

Inside the complex, we visited the Haroldo Conti Cultural Center for Memory, named after an Argentinian writer disappeared in 1976. An exhibition at the Center, “Nuestra Urgencia x vencer” (Our Urgency to win) by Kena Lorenzini, is a feminist photographic essay documenting the struggles of Chilean women at the end of the dictatorship. I particularly liked the pictures from 1984 of women fighting the state by any means available.

The Center also has a section dedicated to Conti. My dad and I read a letter that Conti wrote in 1972 to the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, where he rejected a scholarship offered by them. He writes that such a scholarship is part of a policy of cultural colonization being carried out by the US. Then he says that US imperialism and Latin America are antagonistic to one another. He writes, “My great opportunity right now is America, its people, their struggle. The teachings and the path that were shown to us by Ernesto Che Guevara.”

After Cecilia Vicuña’s “Cartas de amor,” 1964

We visited the MALBA (Buenos Aires Museum of Latin American Art) and went to Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña’s retrospective exhibit. I love Cecilia Vicuña; her poetry and art. The exhibition has Vicuña’s art starting in the 1960s until today. Her work is powerful. Given what I learned about glaciers in El Calafate, I was particularly drawn to a huge 2006 red wool installation called “The Blood of the Glaciers.” I also loved a video she made in Monserrate, a mountain in Bogotá. The video is from the 1970s and she is asking random people what poetry means to them? My dad and his mom have told me stories about going to the mountain back in the 40s and 50s and 60s and 70s when it was not “developed” and people had to walk up the mountain. Monserrate has changed greatly. I always take the cablecar all the way up, and seeing it in Vicuña’s video made me nostalgic for a past I never knew.

There is another video in the exhibit. A recording of the 1974 London Arts Festival for Democracy in Chile, which Vicuña co-organized, where she is talking on the microphone about her and her comrades’ organizing efforts. Then, addressing “all artists and intellectuals” she says, “we need you.”

What was true 50 years ago was true before then and is still true today. For instance, in homage to Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali — who in 1969 created Handala, a 10-year-old Palestinian refugee boy drawn with his back turned to the reader and his hands behind him — many cartoonists have been publishing their characters in that same position in solidarity with Palestine. PQ and I did it, too with the characters of our webcomic, Gumdrops.

After Cecilia Vicuña’s “Arte, arma, ármate de arte,” 2023

I am inspired by the final poem of Andrea Abi-Karam’s book, Villainy, after Cecilia Vicuña herself: “i ask questions like // how to weaponize my own body // or what’s left // of it how do we weaponize our selves // how to weaponize the poem (words as weapons) // give the poem teeth”

I love this. It reminds me of a 2023 Vicuña painting at the museum where she combines the word art and the word arm, concluding, “arm yourself with art,” — ármate. The painting is based on a collage she made in 1974. As relevant then as it is now.