El Calafate • Torres del Paine • Perito Moreno

In Enter Ghost, Isabella Hammad writes, “If we [Palestinians] let disaster stand in our way we would never do anything. Every day here is a disaster.” On this topic, her protagonist reflects: “Resilience is not the same as detachment.” I thought of this distinction as I looked down my little airplane window at the immense Andes mountains extending south into the horizon like endless white waves.

We arrived in El Calafate, region of glaciers and ancestral land of the Tehuelches, on day 102 of the Israeli attack on Gaza. Wael al-Dahdouh continues to report from the ground after being wounded and after losing his wife, three of his kids and eight other relatives to Israeli airstrikes. Refaat Alareer is missing under the rubble of his house, killed shortly after re-sharing his poem If I Must Die; I met Refaat online ten years ago when at Sangría Editora we republished a text of his about his brother Mohammed, who was also killed during an Israeli military operation in 2014. Bisan is still reporting from Gaza, sometimes with bombs thundering in the background. We are witnessing immense resilience in the face of immense adversity. And everyday I see people taking the streets and boycotting and disrupting across the US, acting in solidarity with folks resisting in Palestine and pushing our government to stop funding this genocidal attack in particular and the Israeli occupation in general.

El Calafate

Named after thorny dark bushes covered in somewhat sweet, somewhat bitter little purple fruits filled with many seeds, El Calafate is a beautiful town located where the great Lake Argentina meets the Patagonian desert. 30,000 people live there in wood and prefabricated houses with triangular roofs braving the arid weather and winds that can oscillate between 60 and 70 km/h. The summer vegetation consists of dry grassy plains called “estepa,” calafates and other types of bushes everywhere, with white and yellow daisies growing wild along with another kind of small yellow flower, and no cacti anywhere. On a clear day, we could see the white peaks of the Andes mountains to the west, rising behind the brown mountains surrounding the lake.

My father and I rode horses together and I felt so happy. We also ate calafate ice cream every day :) We walked at night on the main street under the half crescent Moon admiring the big roses of various colors that people keep in their gardens. We went to the wetland, where horses are chilling with hundreds of birds, including pink flamingos. (The water freezes during the winter and the wetland becomes an ice skating ring.) Beyond the tall grass of the wetland are the sometimes green, sometimes aquamarine waters of the huge Lake Argentina, which come from the melting glaciers and feel very cold on the feet.

I loved a museum that we encountered trying to find shade from the midday austral Sun, el Centro de Interpretación Histórica (Historical Interpretation Center). What a great name. The museum visit begins with the history of Patagonia starting 100 million years ago when dinosaurs roamed the earth, and it showcases several dinosaur skeletons found in the area. The museum then displays skeletons and replicas of mega mammals before turning to us, Homo Sapiens, 200,000 years ago. The museum tells us that 14,000 years ago the first humans arrived in Patagonia. Imagine 14,000 years ago, when the history of colonialism in the Americas is only 500 years old.

The indigenous peoples of Patagonia are the Mapuche, the Gününa Këna, the Tehuelche, the Alacaluf, the Selk’Man and the Yamana. There is an entire room in the museum called Genocide and Alternatives for Survival that has a dozen blown-up black and white pictures of different indigenous peoples (pueblos originarios) from Patagonia, and several excerpts from letters and news articles describing the horrendous suffering to which they were subjected by the colonizers — from concentration camps to medical experiments to public exhibitions of their body parts. A letter sent to Europe in 1899 by a Portuguese settler reads, “if we are able to capture Indians this winter I will try to save a girl to send your way.” The museum also tells stories of those who rose up against the rule of the colonizer — demonstrating immense resilience in the face of immense adversity.

East of Lake Argentina is Punta Walichu, a grouping of giant rocks overlooking the lake that was shaped by glaciers and which, at 80 million years old, is older than the Andes mountains. I could see different colors on the huge rocks, marking the passage of time and different sedimentations. The rocks themselves are impressive, and what is most wonderful to me is that there are 4,000-year-old paintings on them.

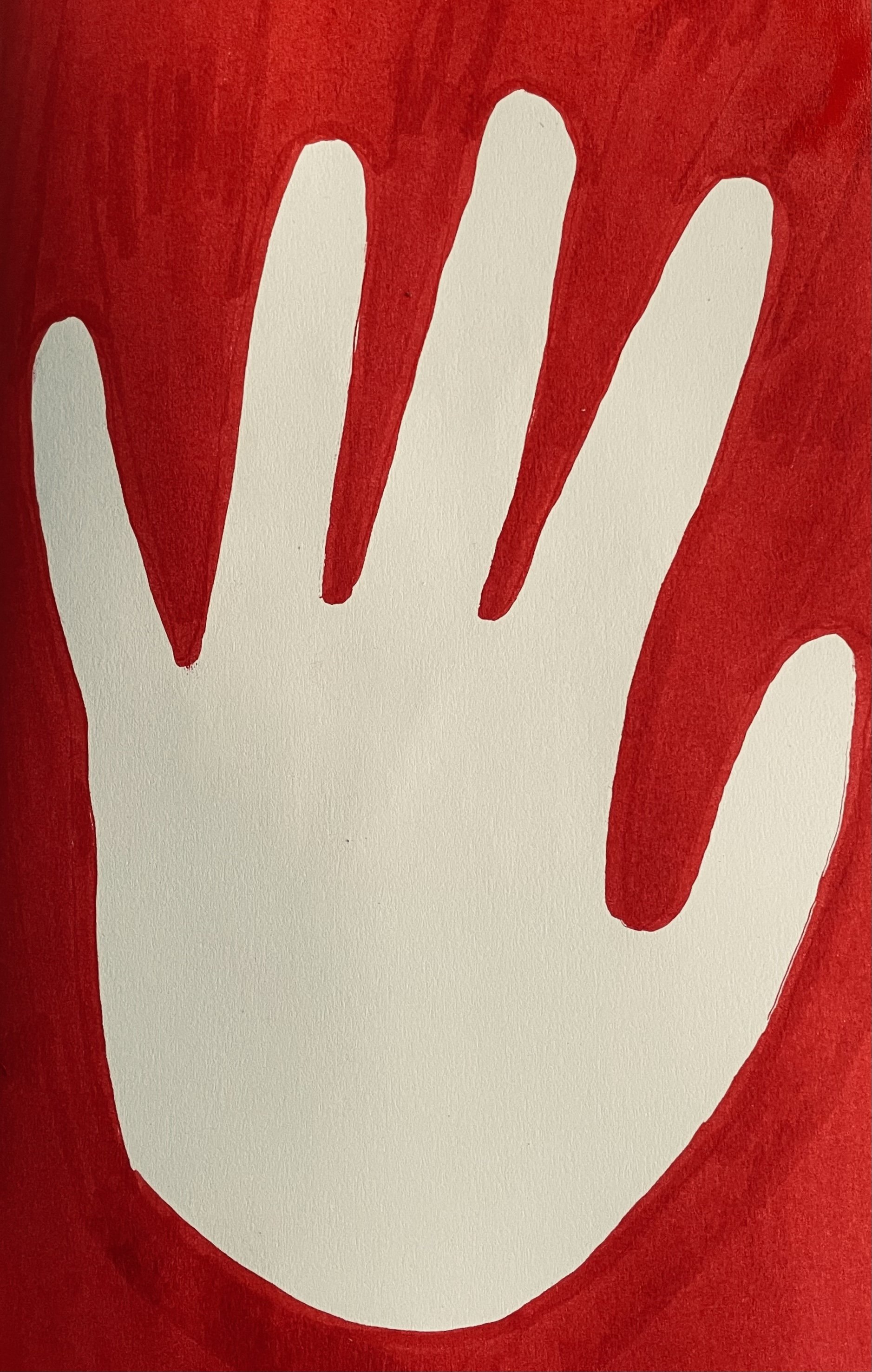

Punta Walichu was named by an Argentinian scientist who came across the paintings; in Quechua, Walichu is a place with caves said to be located somewhere on the rocks. The paintings were made with earth pigments mixed with animal grease (pumas or a type of Patagonian camel called guanaco). Urine or plant-based ammoniac was used to set the paint on the rock.

To make the art, the painters made brushes with guanaco hair or painted with their fingers and hands. There are different colors, mostly shades of red, and there are paintings of humans and guanacos and pumas and one of a human-bird. My favorite type of paintings were the ones made by covering the rock with one hand and blowing the pigment on top. We saw a few of those, including with child-size hands. We learned that this type of art has been found on rocks across the world. We also learned that for Tehuelches, Orion is a guanaco on the move and the Milky Way is the dust that rises behind it.

Punta Walichu

We went on two day trips. One to Perito Moreno Glacier and one to Torres del Paine (Torres means towers in Spanish, and Paine is the Tehuelche word for blue), both located in natural parks. Riding south on Route 40 on our way to Torres del Paine, ancestral land of the Tehuelches, felt important to me because it is there where I imagined I would go in Patagonia. The angular granite peaks rise up between the mountains like a three-tower avant-garde cathedral shaped by glaciers, formed by hot magma that found its way to the surface of the earth 13 million years ago.

On our way back to El Calafate we listened on the radio to Mercedes Sosa’s celebrated song Sólo le pido a Dios (All I Ask from God): “que la guerra no me sea indiferente” (that I am not indifferent to war). Through the window, we saw the vegetation become less green as we drove away from the Pacific Ocean and back into the desert. There were many guanacos running free, condors flying above us, riders on their horses cantering in the horizon, birds that look like smaller ostriches, and also cows and sheep. We stopped by bright blue Lake Sarmiento, one of the places where cyanobacteria (a unicellular organism) first used photosynthesis, creating life on this planet.

Glacier Perito Moreno

The 254 km2 Glacier Perito Moreno is one of the most wonderful things I have ever seen. It was named after the same Argentinian scientist who named Punta Walichu. It rises 70 meters above the water of the southern arm of Lake Argentina and continues 120 to 160 meters below it. We admired the white and blue wall of ice rising in front of the Andes mountains, and saw big chunks of melting ice falling into the water from the top of the glacier, roaring on their way down, roaring as they hit the water.

The glacier has been significantly receding since 2020 due to global warming and, according to the Glaciarium Museum in El Calafate, the climate crisis will bring more melting of the glaciers, more food and water shortages, more epidemics, more droughts and wildfires and floods, more frequent and stronger storms.

We are all connected. We know that the carbon emissions from Israel’s attack on Gaza have an immense effect on the climate catastrophe, for example. And I write this while the mountains and wetlands in my native Colombia are burning out of control.

I think of Isabella Hammad’s notion of resilience beyond detachment, and I am reminded of the opening of poet Andrea Abi-Karam’s book, Villainy: “THE END OF FASCISM LOOKS LIKE // CENTURIES OF QUEERS // DANCING ON THE GRAVE OF // 1. CAPITALISM // 2. THE STATE // 3. COLONIALISM // 4. NAZIS // 5. RACISM // 6. OPPRESSION”. To which they later add, “I WANT A BETTER APOCALYPSE // THIS ONE SUCKS”